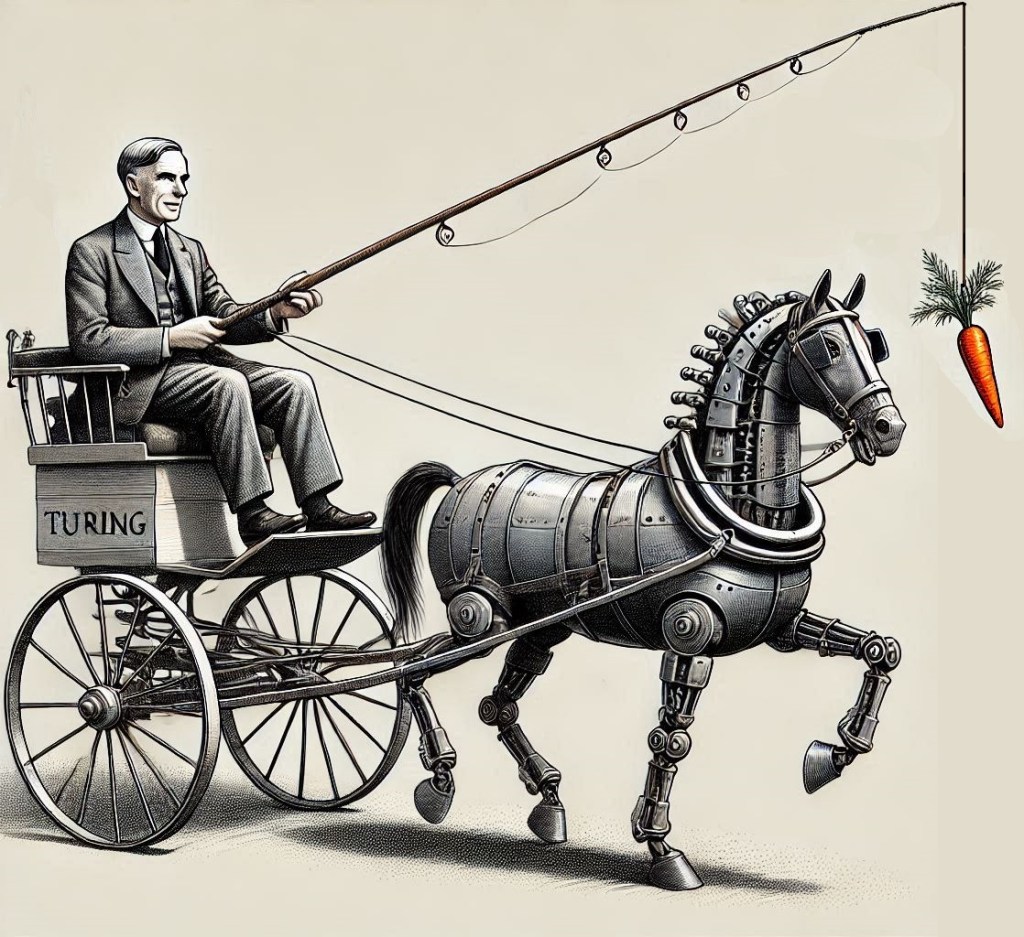

Giving AI the ability to read and write is a turning point in the course of its development, going far beyond its ability to see and imagine. Will our life purpose and meaning be lost in the next few years as a result of generative language models such as ChatGPT?

ChatGPT is the AI language model that took the world by storm at the end of last year. It is to text what OpenAI’s equivalent offering DALLE-2 is to images: ChatGPT takes in a bunch of words, and it spits out something new in response. These two releases have, in a short space of time, managed to make OpenAI almost a household name – an honour few tech companies can lay claim to – and this has had a significant effect in demonstrating to ordinary people everywhere how generative AI can and will be used as part of their everyday lives. The impact of its release was so great that companies such as Microsoft and Google rushed to release their own “chatbots”, for better or for worse.

The release of DALLE-2 brought about a flurry of interest in the use of generative AI for image editing and generation. Generative image editing subsequently became a core part of major photo editing software such as Photoshop. Yet, it’s arguable that ChatGPT has far surpassed DALLE-2 in both its impact on society to date, and in terms of the post-quake societal tremors that are yet to be felt.

So what is so special about generating natural language, you may ask? Isn’t a picture worth a thousand words? Text and images – they’re both just two forms of data…

My response is that although other animals possess the ability to see, and to conjure up visual scenes in their heads, no other animal has to date demonstrated evidence of being able to communicate at the same level of complexity, richness, and hierarchy as a human being. This is solely due to our gift of language: our unique ability to communicate with each other in such a sophisticated way is almost certainly the reason for the success of our species. Communication between humans allows for the transfer of knowledge, and it unbridles us from what would otherwise be a major evolutionary bottleneck: other species can only learn about what they have experienced in their lifetimes, whereas human beings can stand on the shoulders of those that came before them and leverage the knowledge and understanding acquired through their lives to get a major head start. Evolution can only teach through embedding hard coded instincts. Brains did something to address this problem, allowing a living organism to change over the course of its lifetime in response to external stimuli. Evolution has given each living being with a brain free rein (within limits) to change their own “soft” instincts and learn and forget behaviours in their lifetimes that would otherwise take an inordinate amount of time to “learn” through tiny incremental modifications to our genes. Once an animal dies, the knowledge and change they have carefully curated through their lifetime usually mostly dies with them. But – crucially – not if we are able to pass it on to others in an efficient and specific way: through language. Language exists to help us express our knowledge and understanding of the world and has allowed collective human knowledge to transcend the ticking timebomb of mortality: words really do live forever, as long as there is someone there to read them.

Our ability to interact with AI models through the medium of language has – in one fell swoop – put them on equal footing with other humans. These models now have the ability to transfer knowledge to us, and in turn – learn from us. We have, as it were, done the same for these models as evolution did for us when it gave us the gift of language. We have opened the digital evolutionary floodgates to allow AI models access a wealth of data and continual learning – a new era of AI. Previously, the data used to train models would have to be carefully chosen and curated and models would have to be trained from scratch almost every time (much in the same way that animals would need to have start afresh each time they were born – but now that models possess the ability to communicate – and indeed remember and summarise information – there are no bounds on the data they can acquire and learn from. Experiences can be condensed, and information can be neatly parcelled and passed on second hand, without the need for the expensive and unreliable process of reliving events in the first person.

AI models also have three insidious advantages over human beings. The first of these is that they are unlimited in the amount of time that they have available to learn: a model can and will persist and incrementally improve over years, if not centuries, until its own knowledge and understanding far surpasses that which any individual human could hope to acquire in a mortal lifetime. Secondly, human beings are limited in terms of the “hardware” they have. We cannot, as of yet, adjust and update the structure of our own brains very easily, which would require genetic changes. Humans must rely on small, incremental – and often random – changes to their genome to produce changes in the architecture of the brain. In contrast, we are able to change the architecture of AI models at a lightning-fast pace. If a particular part of a model is sluggish, or suboptimal, and is hindering performance, we can swap it out for another at lightning speed. If we identify a new way of doing things that results in improved performance, it can be almost instantly passed on to every model in existence, effortlessly. There will be no need for endless cycles of complex mating rituals or the tedious raising of children. The third advantage is a corollary of the second – AI language models can be instantly duplicated. Although a human child has to carefully nurtured and then let loose in the world for years on end to allow it to adapt to overcome and alter its base evolutionary instincts, anyone who uses a computer knows that if you want to copy some files from one place to another, it’s not exactly a decades-long process (even if it seems like it sometimes).

The ultimate conclusion? AI models will – if they have not already – become the most “intelligent” entities on this planet. They’re destined to beat us at our own game on a playing field of our own making.

Of course, this is all well and good you might say, since the gift of intelligence that we bestow upon these models might be used for the betterment of humankind and to make our lives easier (rather than destroying the world). But as we know from human history, what one person or civilisation thinks is good for themselves and everyone else, may not necessarily be. There has not been enough time for the possible consequences of having entities that are able to do everything that we do, but better, to be adequately mulled over by wider society, due to the exponentially increasing speed of development of this technology.

If you asked me the question of whether we should continue to develop AI five years ago, I would have been completely adamant that we needed to do everything in our power to understand intelligence and to achieve artificial general intelligence, since it would have been a major step towards answering key philosophical questions: how we think (the well-defined part) and defining the source and nature of the enigma that is self-awareness (the ill-defined part). However, it is becoming evident to me now that there is another – more subtle and dangerous – implication when thinking about progress in AI.

Let’s take a slight detour for a few seconds and think about social media. Social media was a human invention that was intended to make our lives better through better connecting us and making it easier for us to talk to one another. The practical implications of social media do seem to have been positive in terms of the abilities they endowed us with to do good things in the world. Social media made it possible for lots of things to happen that were not previously possible, such as getting in touch with relatives, colleagues and friends from across the planet. But what has been the effect on our – admittedly advanced – but still firmly animalistic brains, choc full of instincts and feelings lent to us by evolution over the years to help us survive in a world that existed long before human beings had begun to farm the land, or could even conceive of smartphones – let alone use them for hours on end each day.

The answer is that it does not seem to be all that positive: social media connects us to everyone, everywhere, all the time, and in doing so means this means that the attention we can pay to any one person or experience is diced up like an onion and scattered everywhere. Sadly, for human beings, we cannot divide our attention without negative consequences: if you split your attention in half and focus on two tasks at the same time, you will perform both worse than if you focused on one and then the other alone. Imagine a master musician trying to play both the piano and the trumpet simultaneously: if she were really good, she might be able to play something reasonably tuneful, but she would probably never be able to give a virtuosic – or even “half-virtuosic” performance, whereas this would not be the case if she were devoting her attention to just one instrument at a time. Attention is a limited resource and if we overload it, it starts to slow us down.

Social media robbed us of things vital to human wellbeing: attention, physical connection with others, and the ability to be truly alone. But, AI rob us of something more crucial… Imagine a world where we are fully supported by AI. Indeed, AI does everything for us – it produces delicious food, heals our ailments, does the chores that nobody wants to do, and much more. It might seem like a utopia and that’s because the goal of human beings has always been to make life easier and more predictable so that we can plan our actions with better certainty and purpose. But is it really so? Although this does seem to be a utopia – in that everything is effortless and simple – it completely neglects an essential part of the human condition: the need for purpose and meaning.

Meaning is life’s apology for our imperfections. With our imperfect understanding of the world, we have developed a natural curiosity – almost an addiction – to understanding what matters to us in the world around us better. It may be that it is a fool’s game, and some things are simply impossible to “understand”, perhaps because they are ill-defined. But the belief that we can always continue to improve our understanding and that we are on a level playing field with everyone else gives us hope. Without hope we have nothing to look forward to! Once AI can paint better than us, can tell us why we’re doing our job wrong, can patiently and helpfully correct our creative endeavours with all the patience and patronising manner of a good-natured parent helping their child, how will that make us feel? Will we feel blessed to be taught and educated by AI? Will we feel pampered and comforted by AI giving us everything we wanted and dreamed of? Maybe we will. But in gaining these wonderful benefits, we will have lost something that is at the heart of the very essence of what makes us human beings: our natural curiosity.

What is it that makes us learn new things and explore things we have never previously experienced? It’s a natural tendency to get bored and the sense of reward that comes from feeling that we are growing and developing and getting closer to some ideal vision of our future selves. We want to learn to use that knowledge to better understand ourselves. Life is interesting because it is mysterious, because it unpredictable, and because we don’t know exactly where it is heading.

But when AI can do all the exploring for us, then what is there left for us to do? When we know that instead of thinking deeply about a problem and coming up with our own personal understanding, we can outsource the job to a powerful entity that can do it much faster and better than we can, then what happens? Will we bother to think at all? Will we still have a natural curiosity, or will we come to the terrible realisation that all that we want to know and understand is already known and understood by models that are far wiser, more intelligent, and proficient than we could ever hope to be. Models that can explain the intricacies of our own brains and existences better than ourselves. That desire to express and communicate the inner human condition and experience has inspired countless beautiful pieces of art, writing and music. But when this sort of stuff can be produced at the press of a button, will there be any point in producing more of it? When something that took half a lifetime to brew and a quarter lifetime to create can be conjured up instantly, then how will we feel?

Human beings are proud animals. I’m sure that you and I both believe, deep down, that we understand lots of things in a unique way, and that we are fairly knowledgeable and curious. When we see something that we have never experienced before, things go one of two ways. At first, we are naturally curious and will try to understand it better. If we find we are learning in a meaningful and pleasant way, we tend to gain immense reward and satisfaction and develop a deep passion for that thing. But, if we can’t understand it, we often become frustrated, and ultimately angry and spiteful, eventually abandoning the whole project because it’s difficult and unsatisfying. It’s not a fault – but rather it’s simply part of human nature.

When problem solvers (AI) exist that can operate with mental resources that infinitely exceed our own, then the problems that they solve may, sadly, be incomprehensible to us. It might be that we have understood the world so far at a level that seems sophisticated, but is actually only meaningful to us because our relatively limited brains are capable of processing that much information at once. Maybe the great mysteries of life and the problems that haunt and fire us up today do indeed have solutions and explanations, but those explanations might require bigger brains to process. For a dog, it might be a relatively remarkable feat of ingenuity and intelligence to be able to open a door. Perhaps we as humans will simply become screaming toddlers in a world whose reins we have handed over to AI teachers, who smile upon us with all the loving gaze of a parent watching its child try to use a spoon for the first time. Perhaps we won’t even realise it has happened.

Despite complexity of the problems that exist today related to bettering our self-understanding and our understanding of the universe we live in, all these problems seem somehow tenable; we feel as though because other human beings have been able to come up with them and explore them, we too might be able to. But when we see that there is something that isn’t human that is able to do things better, will we become jealous? Will we lash out and destroy the thing? Will we simply meekly accept our fate and live an existence free from the burden – and beauty – of self-exploration and discovery? Will we lose meaning in our lives, or perhaps we – the incessant explorers and innovators – will come up with a new definition of what it means to be human.

Leave a comment