This is a little different to Le Carré’s usual fare. Much less a spy story – although the ghost of espionage still lingers. If you are looking for a fast-paced, action-packed thriller, this is perhaps not the book you are looking for. Though at times this is present, Le Carré’s style is much slower and more deliberate.

The novel follows the plight of the eponymous character, The Constant Gardener – Justin Quayle – a fundamentally decent British civil servant posted to the High Commission in Nairobi, Kenya, whose young wife Tessa is killed while out in a Jeep with her supposed lover Arnold.

This event completely upends Justin’s life and sets him on a path of discovery, asking who murdered his wife and why. But peeling back the surface layers, he discovers that not everything is what it seems and that corruption and greed lie buried, deeply rooted. He soon learns that a little knowledge and curiosity is a dangerous thing, as the very people who killed his wife set their sights on a new target.

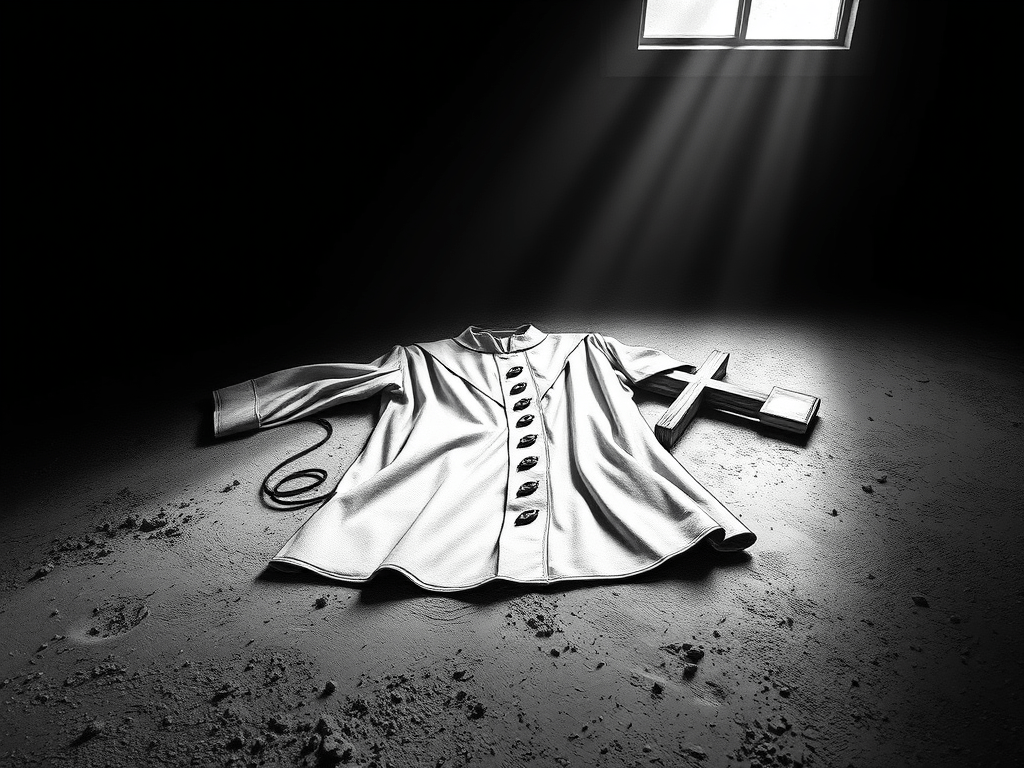

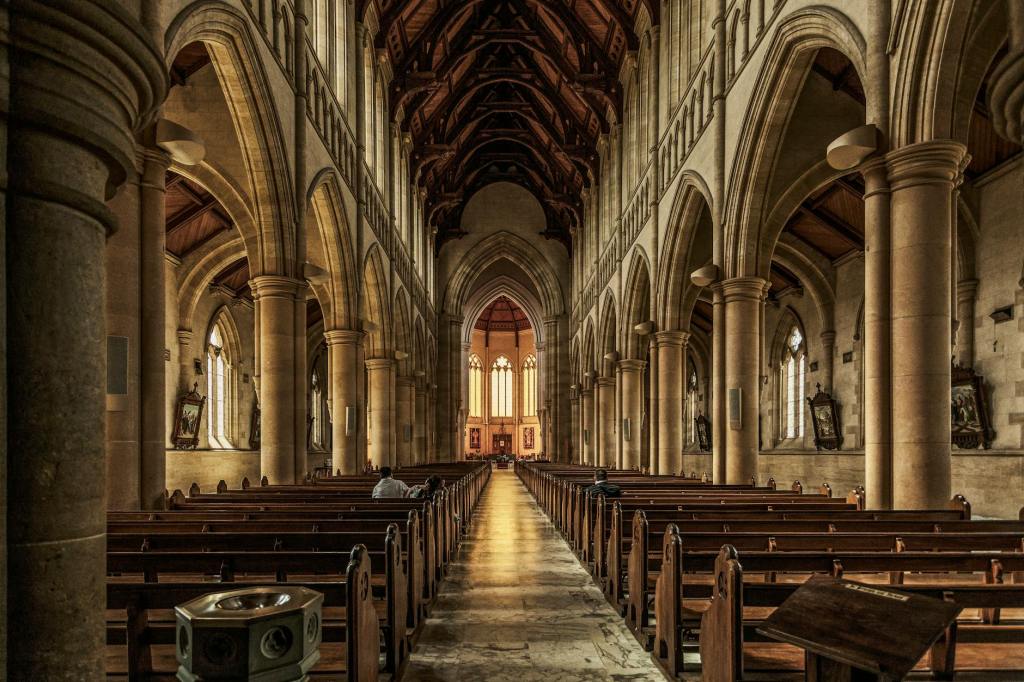

Materially, the book is about the evils of large, multinational pharmaceutical corporations, specifically their exploitation of the citizens of third world countries. Testing of dubious medicines, “angelic” offloading of old drugs (for tax breaks), and the prioritisation of profit over people being their main sins. Of particular interest is the flawed character Lorbeer, whose sense of morality (derived, it seems, from his Christian upbringing) is at odds with what he evangelically terms “the God Profit”, as well as his need to insure himself. Lorbeer is brimming with guilt. But guilt alone is not enough. It is only when guilt leads to good that redemption is achieved, to quote Khaled Hosseini in The Kite Runner. Guilt taken on its own is salt on an empty dish – it is a selfish, bitter emotion. Though Lorbeer scratches this itch through an occasional bout of self flagellation and confession, once he has paid his dues and his moral debt is settled, he inevitably falls back into to his vices.

Le Carré shows that it is not just big pharma that can be evil when it worships profit. Rather, it is also the state actors and governments that implicitly support them and are therefore complicit in the crime, in their effort to appease their financial bedfellows.

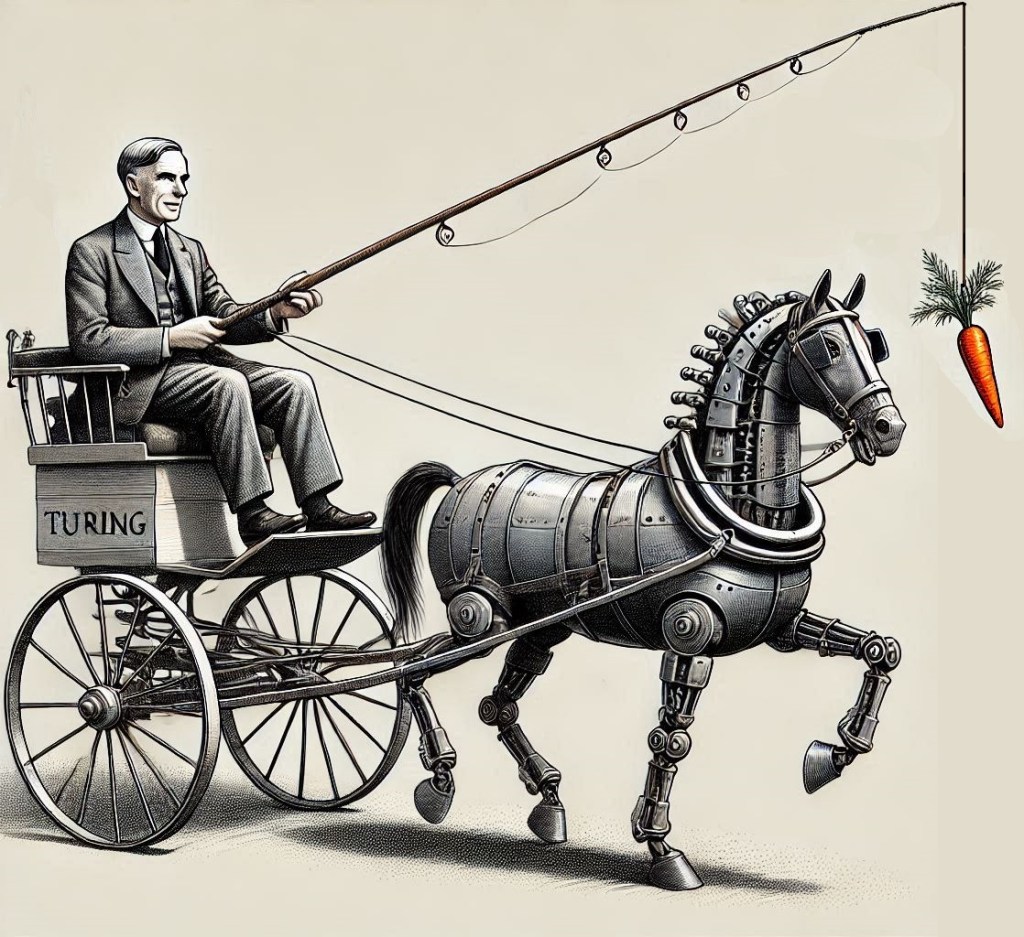

At the heart of Le Carré’s writing is the notion of conflict of loyalty. Justin’s loyalty to his country and his commission – his need to maintain the status quo (Tessa married “convention”), which comes to be at odds with his enduring love for his deceased wife. While they are married he makes a deal with her – one which he later sees as being born of his own cowardice – that Tessa can continue to fight her battles while he suspends his disbelief and ostensibly toes the line. Loyalty, love, and betrayal are three sides of a triangle. Loyalty is duty to that which we love and to quote Le Carré: love is that which we can still betray.

The beauty of Le Carré’s writing is the acerbic way in which he captures the essence of the human condition through the personalities that he brings to life in writing. Whether it be Sandy Woodrow, the lecherous civil servant whose childhood never ceases to be an excuse for his misbehaviour; Western liberals who “do not let their ignorance stand in the way of their intolerance”; or one of my favourites – to quote a character whose very utterance of this phrase screams irony – the people whose “idea of ethics is a small county east of London”.

As long as there is conflict of loyalty in one’s life – whether it be conflict of “conscience with corporate greed”, love and country, or guilt and profit – we will remain human and Le Carré will continue to be relevant.

Leave a comment