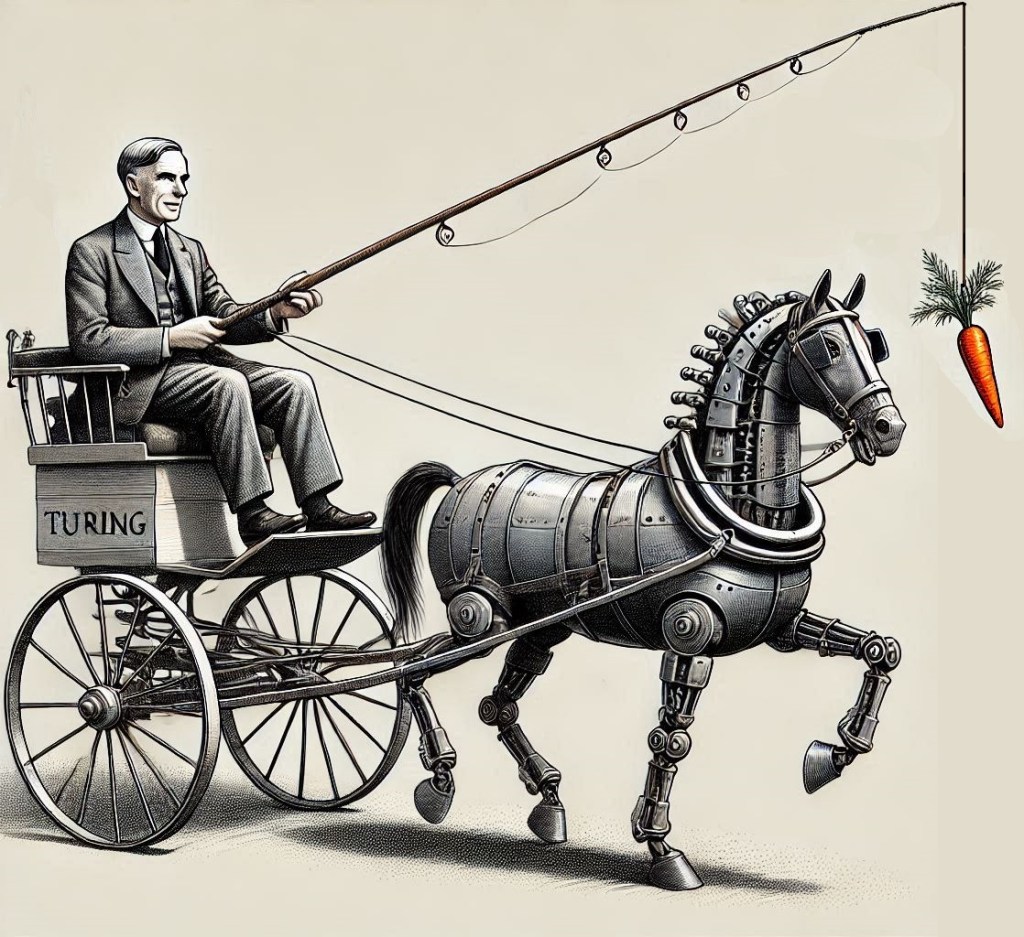

The Turing test is a carrot on a stick for AI, driving progress forwards, but always just out of reach. Image credit: artificially generated.

We humans are lazy. We are constantly looking for ways to avoid having to do things. We started off early and eager, inventing tools that made the work we had to do with our hands redundant, doing physical work for us. Symbolic thinking brought with it a whole different field of play and we began to use the environment to offload some of our mental exertions by – for example – using calculators to do our mental maths or using sheets of paper as mental chalkboards, allowing our thoughts to persist without having to tax our slothful brains. We are so desperately fond of being lazy that we are trying our utmost to invent machines that replace our thinking entirely in the form of AI.

Yet the growing intelligence of our own handiwork is bringing to light interesting philosophical questions. Will our performance being outmatched on a much wider range of domains than seen previously detract from our lives? Will it kill the joys of creation and creativity and the satisfaction one gains from putting knowledge to work to engineer new inventions? Or will we content ourselves with marvelling at the creations of the machines we have built and reading the writing of beings smarter than us? To answer these questions we have to first know the answer to a more fundamental question: will we ever get to the stage where AI is smarter than us? But I don’t actually think that that’s the right way to phrase the question. A better way is: will we ever admit to ourselves that AI is truly our equal?

With the recent release of ChatGPT’s o3 large language model, which – hype and eye-watering costs accounted for – does manage to achieve an impressively high score on François Chollet’s ARC-AGI benchmark (purportedly a good test for abstract thinking), one wonders where we will draw the line and say “this is it – we’ve created general intelligence”.

Will it be when we create a machine that behaves exactly like we do – in essence, recreating ourselves? Is the human desire to reproduce so strong that we wish to find more and more efficient ways of engineering our own behaviours simply because those behaviours are what have proved conducive to our survival? Is there anything inherently superior about “super-intelligent models” other than the fact that they are capable of explaining things to us and surprising us with their abilities in ways that we would not have thought possible (i.e. being unpredictable)? Maybe it is exactly this surprise factor that we are searching for.

Despite huge leaps in the capabilities of machines that think for us, it seems that every new advance in AI, however astonishing, is eventually met with backlash and naysaying which aims to discredit the newest advances and explain them away as sterile, mechanical reasoning. But this says more about us than it does about the technology. It exposes our bias in thinking that human beings are special. Anything that comes close to behaviour that we see as similar to our own is always going to be seen as somewhat magical, because magic is what we cannot understand. We may have evolved to believe that our minds are unique and mystical, going so far as to endow them with what have gone by many names, but are commonly referred to as souls. But is this all an illusion? In Sentience, Nicholas Humphrey claims that the brain evolved to “methodically bamboozle” the inner self, isolating it from the backend machinery of the mind to trick it into placing a high value on its own magical and unique existence. But just because being shown magic to believe in our own value is evolutionarily advantageous, it doesn’t mean that this magic is all an illusion: perhaps, in evolving to bamboozle the self, the brain took the path of least resistance and created something that truly was magical and cannot be understood – real magic, rather than smoke and mirrors.

A lot of problems in the world would be solved if human beings simply better understood other humans. But yet more would be solved if people understood more about the most important human being out there – oneself. We understand very little about ourselves, even when we think we do. For instance, nobody really likes getting angry, sad, disheartened, or depressed, and so often our logical minds tell us that our negative thinking is irrational and even counterproductive, and yet we feel these feelings anyway. Our minds are only partially – if at all – under our control. Due to our poor ability to predict our own behaviour, let alone that of others, understanding the self and the mind has long been a holy grail for humankind, even if we are not consciously aware of our pursuit of it. Neuroscience, philosophy and psychology are the obvious choices of means to this end, but in fact I would argue that all scientific and artistic disciplines are in some way an attempt to explain or express our subjective experience of the world, in order to better understand it, or to help others better understand it. We are ultimately wired to always want to know more about us. Who and what are we exactly? We are a mystery unto ourselves, whether by chance or evolutionary design.

It seems obvious that those things that we develop artificially will inevitably be endowed with at least some explainable properties a priori, because we have designed and created them according to models that we have come up with ourselves. This extends to intelligent systems which we engineer. We can control and explain the behaviour and activity of the individual artificial neurons in neural networks to study their behaviour, so our journey towards building true artificial intelligence has really just been another – perhaps the most important and useful – huge journey of self-exploration, where we have attempted to better understand how the brain works through building one and saying “Aha! That does what we do, so it must tell us something about what we are”. This tells us something about what exactly we believe intelligence to be.

Intelligence is quite poorly defined from an objective point of view, in that it seems to be understood simply through reference to human behaviour and its distinctive qualities. We often define things by either drawing parallels to other things, or by highlighting what distinguishes them, and human intelligence is as much defined by what it is as what it is not. According to widely held intuitive beliefs, it is somewhat like the intelligence of natural things (other animals), but it is different from the intelligence of things we build ourselves (AI). In an effort to assert this statement, we have come up with ways to differentiate between human and artificial intelligence. Initially we coined the Turing test, saying that if a machine was indeed intelligent, it would be able to fool us into thinking it was as part of a conversation. Recently, as that has begun to seem as though it is in danger of failing as a discerning measure, we have begun to come up with more sophisticated problems that humans are capable of handling but AI is not, in order to distinguish the two. Since our definition of human intelligence is somewhat based on distinguishing it from artificial intelligence, the goal of achieving true “human-like” intelligence is therefore flawed by design. It is a carrot on a stick, a shifting goalpost. The benefit is that it drives progress in the field, but the downside is that it exposes our own stubborn delusion in believing that we are and always will be different and special.

If this trend continues, as it undoubtedly will, and we continue to challenge AI to solve problems that it performs poorly at, in order to assert our own dominance, then one day it will be able to do everything that a human can do – and better. Yet, when that day comes, will we still find excuses to distinguish ourselves as superior? Unfortunately, we probably will. We’ll claim that we cannot know for sure whether the AI is “magical” – whether it is conscious. We will do this, all the while professing our faith that other human beings, who are equally good candidates for being unintelligent “zombies”, are conscious without a shadow of a doubt. We only believe other humans to be conscious because we think of them as being like us; because of the brain’s vested interest in wanting us to hold this (verging on delusional) belief, so that we continue to place value on both our and their lives, allowing our species to prosper. The tricky problem of consciousness exposes the shaky foundations of what we think of as human reason and rationality, with the ensuing illogical rubble being quickly swept under the carpet; we are bundles of contradictions and inconsistencies and perhaps that’s what really distinguishes us from other animals, who on the surface of things don’t seem to worry about questioning the nature of what they are and instead just get on with it.

Never have we said that calculators are more intelligent than humans simply because they are capable of solving mechanical problems at a lightning-fast pace. Instead, we claim that those computing machines that we have built, which are by all measures much smarter than us at doing particular things, are simply “narrowly intelligent” – something that we consider to be an inferior form of our “general intelligence”. In this way, we are just inventing excuses to change the rules of the game in order to give us a lead. Like the disillusioned politician who – when confronted with overwhelming evidence of their own failure – convinces themselves that, seen from a different perspective, things are still hunky dory. If we begin to suspect that the magical, supernatural beings that we believe ourselves to be a re not really that special after all, then our brains would have failed in their most important task.

Intelligence is a cat and mouse game – the writing of its definition is a prize a afforded to whichever being has greatest control over the world and is able to most successfully dominate it at any one point in time, winning the freedom to set the rules of play. Since we still have the upper hand over AI (we are still in control of it, aren’t we?), we afford ourselves the right to treat it as less intelligent than ourselves.

And yet, if AI can beat us at chess and if it can beat us at the game of Go, then maybe… just maybe… it can also beat us at the game of life. It is just a question of when. AI will never be able to truly pass the Turing test, because our instinctive human arrogance – the belief that we are and always will be special – will continue to stand in the face of insurmountable evidence and motivate us to find ways to differentiate us from the “inferior machines” for as long as we exist. That’s good for AI, but is it good for us?

Leave a comment