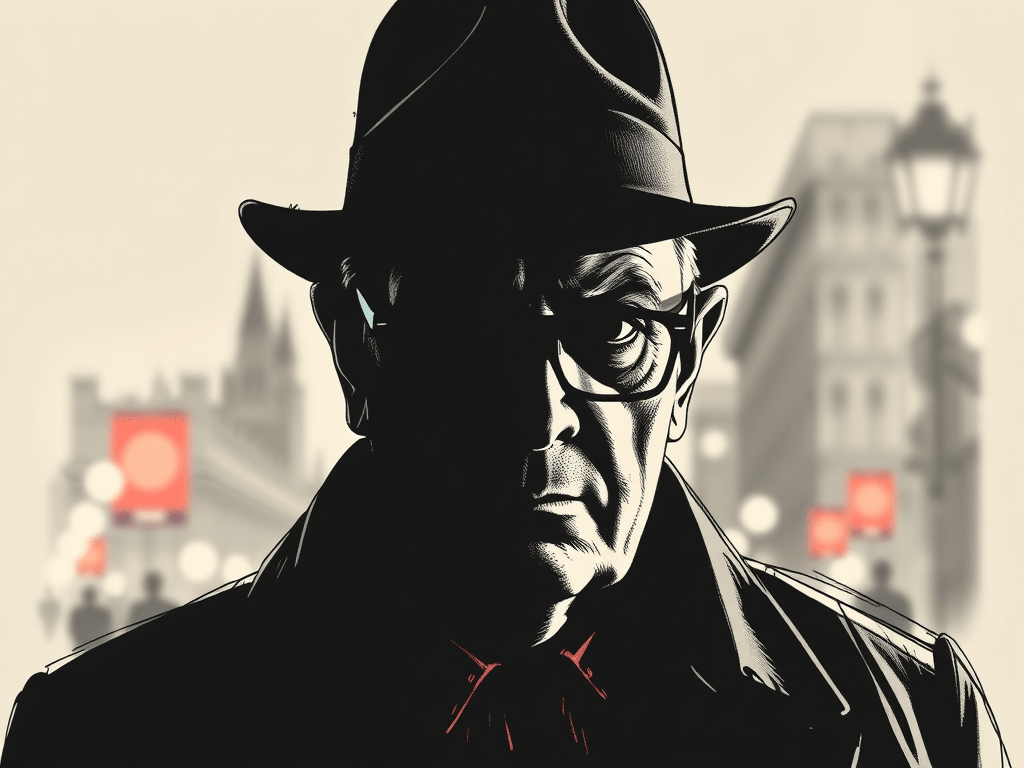

Intelligence work is a game of piecing together knowledge. It’s about weaving together bits of information, while being aware that every piece might not be completely accurate. But what happens when some of the information you’re getting is unreliable, or worse, fabricated? This is a game that the so-called “intelligence” agencies (read – spies) have to play, and it can’t be very fun. Being constantly vigilant, constantly suspicious, of your enemies, your neighbours, your friends, and perhaps even your own loyalty.

A mark of great literature is when it exposes uncomfortable inconsistencies within us. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy ticks those boxes. It’s a book about the search for a double agent – a mole – within the fictitious British intelligence centre, The Circus, so-called because its headquarters are somewhere on Cambridge Circus (I should make a note to look out for the unassuming building opposite the theatre when I’m next there). The mole has supposedly infiltrated the highest echelons of The Circus, and is working at slowly dismantling it from above.

Intrigue and action fill the novel, though I wouldn’t describe it as a fast-paced thriller. Narrative storylines weave and dart through time as well as space, and one finds themselves as easily in the 50s as the present day (of the book), drifting between them in a drunken stupor, attempting to put together the pieces into a coherent narrative. There are decades of pages where not much seems to happen, but then these are followed by pages where decades happen. It goes against the principle of writing for a popular audience, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. It keeps you thinking, and the background and slow burning development is important to make the climaxes all that more intense and meaningful. But where the author really shines is in his deep insight into the human psyche.

le Carré has a talent for painting pictures of people so intensely detailed that it makes you want to stand up and shout your objections if anyone were to attempt to claim they weren’t based on real people. Take Jim Prideaux as a stereotype of a certain kind of British public schoolmaster from another age – and yet his eccentric references to “Juju men” and idiosyncratic French are only the surface of him. Most other writers would have bludgeoned it, and steered clear of certain stereotypes, but le Carré doesn’t. Painting pictures so real also allows you to hold in your imagination two conflicting views, from two opposing characters, and accept them both as good arguments. le Carré’s writing can make you uncomfortable, and even challenge firmly held views about loyalty and the demarcation of the moral battlefield. When the mole is finally revealed at the end of the novel, things do come together nicely, and yet it is intensely painful, for the readers and for the characters.

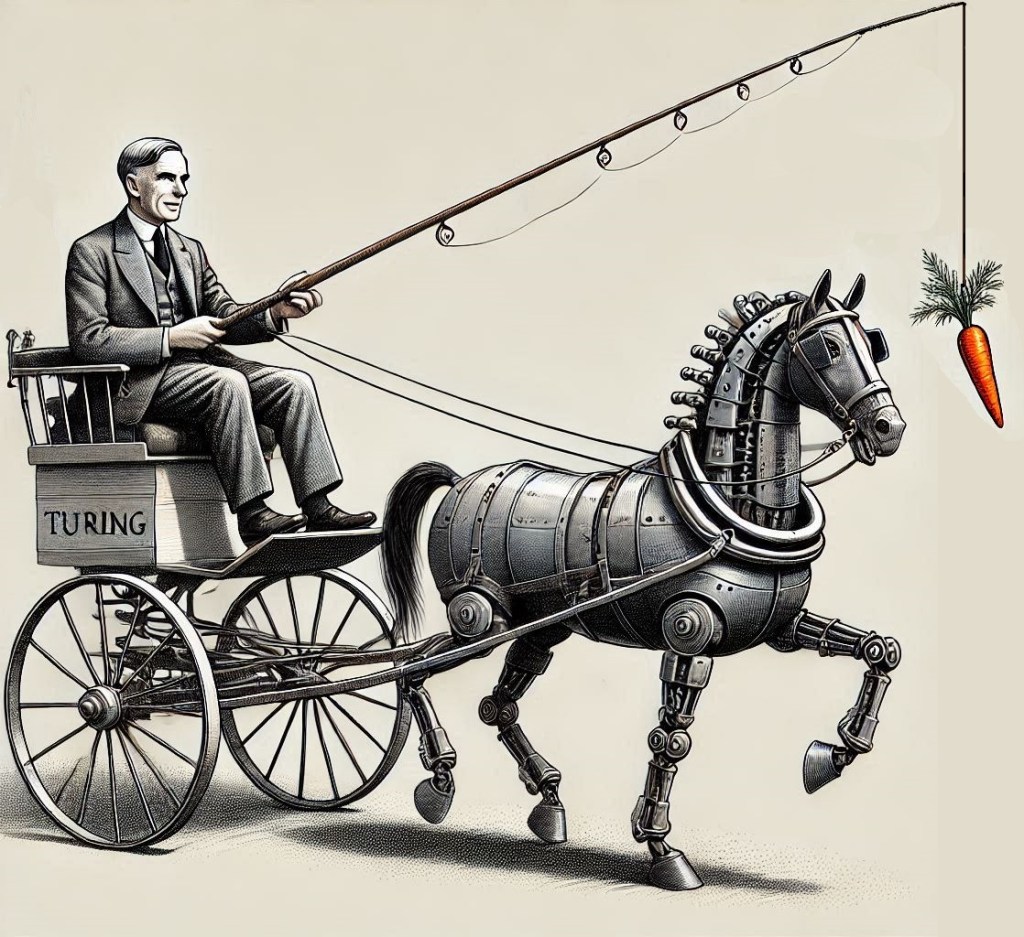

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy provides an account of spying that transcends typical tropes. Every great piece of art contains something of the author within it – that which makes it human. As an aside, whether that means that AI will ever be able to produce anything truly “great” – in the field of literature or beyond – is a different question, but for now – le Carré has undoubtedly poured a significant amount of himself into this book, and it is a unique and valuable account of what it might have been like to be a spy during the Cold War. How accurate this picture is I cannot say, and it is a tribute to le Carré’s skill at realism that I would again be on my feet objecting, but somehow not at all surprised, if he had made a whole lot of it up. But then, books have to, otherwise they might become slightly too real, and slightly too uncomfortable.

Image credit: Generated using AI.

Leave a comment