Reflections on reading The Power and the Glory

It has been a while since I finished The Power and the Glory and I suppose I never got round to writing a review, partly because I wanted to digest the thoughts and ideas in the book. However, I realise that rather than allowing ideas to brew, sometimes leaving them untouched for too long can lead to them festering – the paths that ideas hint at must be actively trodden to be shaped and so sometimes the best way to digest ideas is to use them. Writing a review is one way in which to do so.

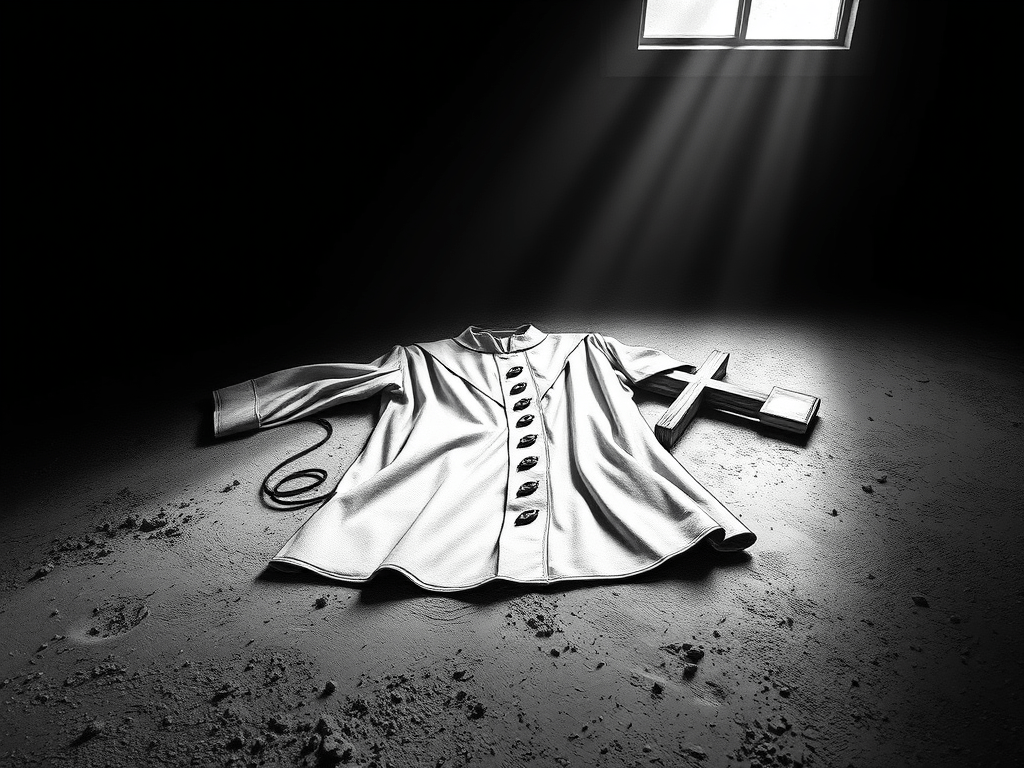

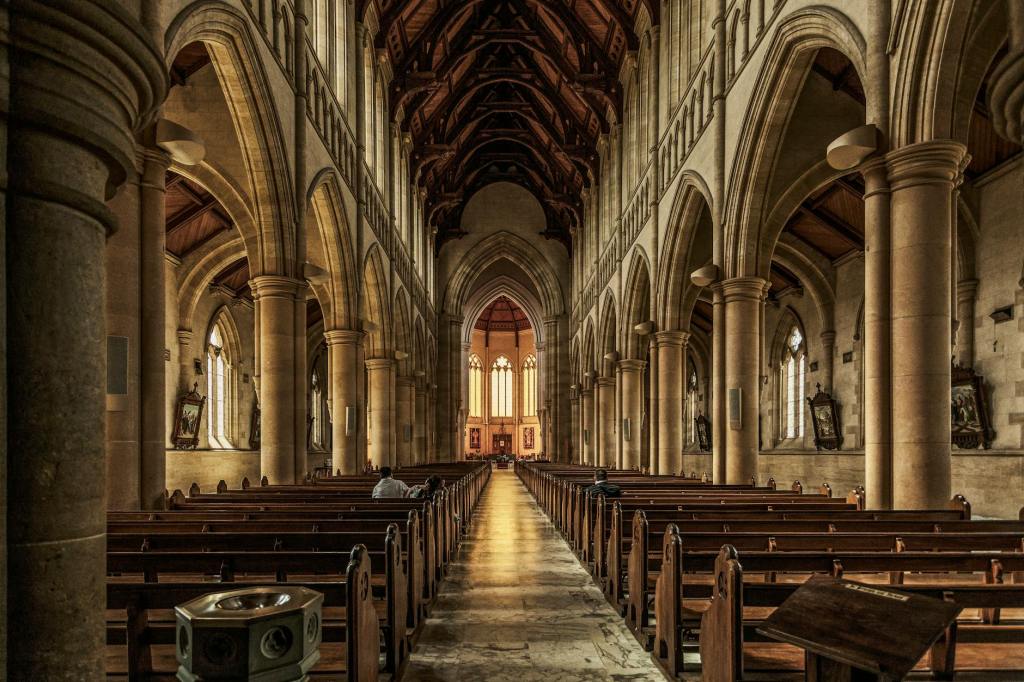

The Power and the Glory is a novel by Graham Greene that introduces the so-called “Whiskey Priest”. This is a phrase I first encountered in the form of the title of an episode of Yes Minister, where it referred to hypocrisy in the Church of England. In The Power and the Glory, Greene talks of the Church, but not of England, instead exploring themes of faith and self-doubt against the backdrop of a historic and liturgically desolate Mexico. The novel is set in the 1930s in the aftermath of the Cristero war, at a time when the country was riven by a civil struggle, particularly in the state of Tabasco where authorities sought to actively root out and punish Catholicism in all its forms, sometimes by hunting down and executing its practising priests. The phrase Whiskey Priest is used to refer to a priest on the run who, though righteous in name and title, has a penchant for overindulging in spirits.

Though I had heard of Graham Greene as a spy novelist – influence of John le Carré and the like – he was apparently also a great Catholic novelist, as evidenced by this novel (and others). In this book, Greene maps the itinerant struggle of a seemingly last remaining openly practising priest to hide himself from the authorities, themselves spearheaded by a deeply anti-religious Lieutenant who blames the Catholic faith for the profound unhappiness he sees in the minds of children and the adults they grow to be. The Lieutenant is a man who thinks Catholicism to be totally and absolutely incompatible with an ideal society.

Our priest, on the run from those who threaten to find and kill him to make an example of him, struggles not only with the constant threat of capture and execution, but also with internal conflict at the intersection of pride and status, an unrelenting alcoholism, a raw physical sin, and a sometimes reluctant yet unwavering faith in the divine eye watching over him that drags him towards choices that the rest of his mind doesn’t always seem to want to make.

I wondered for a long time whether this was a book praising the troubled priest for his faith and constant self-doubt, or whether it was trying to highlight the hypocrisy of a man who refuses to give in purely due to his pride and desire to maintain his belief in his own status as a clergyman, rather than a true and humble faith. I now realise that it is perhaps both.

What is interesting about the unnamed priest is how he is so patently aware of his faults: his delight in being afforded the status of a holy man in a society that reveres the clergy, of deep hypocrisy – notably his vice for drink, and the constant question hanging unsaid: whether image and hope matter more than human life, since while he remains on the run, innocent hostages rounded up in local villages are being killed by the Lieutenant in an effort to pressure the priest into giving himself up.

In light of his faults and his pride in his position as a holy man, can we say that the priest is a good man in the context of his faith? A man who chooses to ignore the authoritative rule and live the life of a fugitive, respected nominally at least by those who feel a thirst for their lost faith, but simultaneously living with the burden of being responsible for the killing of hostages.

Greene notes in the novel that any situation can be lifted up to expose its underbelly of contradictions. Contradictions result from close examination of existing rules, finding them to come up short, and therefore requiring revision. This often happens to us in the midst of our thinking, since our minds are tuned to detect paradoxes and contradictions. Like imperfect forgeries of great artworks, if the general yet convenient rules that we adopt and live by are examined with too close an eye, their revealing blemishes will become starkly apparent and the illusion of their perfection will instantly shatter.

“You only had to turn up the underside of any situation and out came scuttling these small absurd contradictory situations”.

The Power and the Glory is packed full of contradictions, ironies, and contrasts. Many of these are religious ones. Firstly, the thought that if God were made in man’s image, then in order to deface all of God’s image, you would have to kill yourself “among the graves”. Then there is the idea that the presence of vice and evil on earth necessitated a God to die for it: anyone can die for good, but to die for evil, you have to be something special – contradictory and confusing perhaps because of the choice of words. Yet the most striking of these contrasts is that that between the choices of our protagonist priest who refuses to give himself up, and those of another priest in the novel who chooses the opposite – to acquiesce to the demands of the anti-religious law, take a wife, and live the embarassed and meek life of a man whose honour and pride have been stripped of him, publicly renouncing his faith, and complying with the rule of his oppressors. This second priest is the cause of no deaths, beyond that of hope, (religious) faith, and morale.

Understandably, our anonymous protagonist is tormented throughout the novel by self-doubt and intense self-criticism, recognising in himself such faults as cowardice, hatred, hypocrisy, resentment, pride, weakness in the face of temptation, desire, and love. For this, he is the most human of priests. Despite his self-doubt, he struggles on and strives to continue to act as an imperfect vessel through which the Catholic faith can continue to flow, sporadically inspiring hope in the hearts of those whose freedom of faith has been oppressed and who he feels strong enough to uplift. Does it matter that he is not a saint, or that his is far from what might be thought the perfect image, even in his own eyes? Indeed, his intense awareness of what he perceives to be his own faults make him somewhat honest, and honesty is the one trait that is most difficult to practise, above all to oneself.

Yet, is it the priest’s rigid faith or a delicate pride that causes him to continue to struggle and mentally flagellate himself for his alcoholism in a desperate effort to redeem himself and sustain his image before those who might seek to judge him, most of all himself? Sometimes, it seems his pride is the only thing that keeps him going, yet at other times, he seems convinced of his failure as a man of God, reflecting his strong faith. I think that part of the reason it has taken me so long to come to terms with the meaning behind this novel is that I have struggled to understand which of these motivations drove the priest to do the things he did, not realising perhaps that human beings are messy and it could indeed be a mix of the two. But setting this aside, we can also ask – does it matter? Would being driven out of a sense of pride somehow tarnish the good outcomes of what the priest did, compared to being pushed forward by what we might call a “pure” and humble faith? I do suspect it would.

—

Is it wrong to do the things that we do for a particular reason that isn’t what we intuitively know to be pure “goodness”? Put more precisely, what exactly does it mean to be a “good” person at the outset? Do the “good” things that one does have to come from a place that is fundamentally pure and moral? Is such a thing even possible in the first place? The answer is: probably. Most human beings have some form of an internal moral compass – called a conscience – that guides us towards doing things that help the group as a whole to prosper. The more an individual must personally sacrifice for the betterment of our group, the more “good” we will perceive an action or choice to be. We feel rewarded when we do “good” acts and this reward mechanism provide relief to make up for what we must give up in return. But then is doing “good” acts for supposedly selfish reasons: feeling pride, winning the admiration of others around us, or anticipating that something good will also be done to us in return truly “good”? Do ostensibly moral acts done for these reasons “count” as much as acts done that stem from an internal sense of morality and conscience that we might stereotypically associate with being a “good” person?

The truth is, our internal sense of morality is just another reward mechnaism. It only differs from other kinds of rewrad in that it is internalised and by the definition of the mechanism of human morality therefore not looked down upon by society. To draw a gastronomic parallel, eating a bar of chocolate is internally rewarding since we feel good when we do it because our brains are primed to feel that way and reward us for it. The difference between internal and external morality is that our internal sense of morality is largely unconditional – it doesn’t need a particular societal context in order to exist and thrive. Perhaps this is why we value it more – because it requires no outsider actions or prompting to enable it. As such, we might call it more reliable, more stable – an *active* process that is initiated from within rather than passive one that depends on what is without to drive it forward. And yet both internal and external drives for good both achieve similar end results.

Examples of choices with moral outcomes made for selfish or materialistic reasons abound: being a vegetarian because meat is expensive (it’s conditional on the prices agreed by other people); being nice to others because we want something from them (if they weren’t in a position of power we wouldn’t treat them well); saving a dog from drowning while others are watching (since we would look bad if we didn’t and will raise our social capital if we do). These are all examples of moral choices that we make that are dependent on external conditions – social or physical. This leads me to believe that we judge others as “good” or “bad” based not on how they act, but on a belief of how they would hypothetically act in the absence of constraints and biases to act well. That is to say – if nobody was looking, then what would that person do? So to be “good” or “bad” is fundamentally a question of trust – how much do we trust a particular person to be good to us or to others without external prompting? Can we trust this person to be good in and of themselves?

But does trust and reliability seem so important? It’s a question of expectation. When somebody is trustworthy, we can predict how they will behave and know how they will respond to different situations. We know that they will stick to their promises and have faith that they will keep to moral and social contracts that help society to function and empower us to be able to live our lives without worrying about others acting in unexpected or unpredictable ways. For instance, we know that people will drive on the right (which is sometimes the left) side of the road; we know that others will not decide to take our belongings and so we feel more comfortable possessing them; and we trust that the police, politicians, and those in power will not abuse the power we have entrusted them with. Trustworthiness is about sticking to the rules of the societal game of life that we play, and doing so in a way that is not contingent on external conditions (such as somebody else seeing you to judge you for it). This is also why morality is often so strongly connected to the law – the law is a set of social conventions and contracts that groups of people have collectively drawn up and agreed to live under, for the good of the many rather than the few.

Good people are predictable. All happy families are alike. Good people won’t cause us trouble or do things that are unexpected or throw us off course. They won’t say one thing and do another. They won’t try to hide acts from us that they know we would feel offended, angry, or hurt if we knew about. To be good is to be reliable.

So was the priest in our story a good man? The answer is yes – but only to an extent. To understand the degree of his morality in the context we have outlined, we would need to know the degree to which he was motivated to do what he did out of a sense of pride in his social status versus a more intrinsic drive stemming from a deeper faith. Things are not black and white. For example, whether our priest would have done the same thing if he were not afforded respect for his position as a clergyman, we will never know for sure.

Going further, we should ask whether the interpersonal mechanisms such as status and reverence that create the conditions that are sometimes necessary for people to be good are the successes of human society, or if they simply highlight the failure of intrinsic human morality and shed a harsh light on the dark and fragile foundations upon which our beliefs about human goodness stand.

Though we can never be sure what our priest would have done had the conditions been different, perhaps we can open up our hearts and give him the benefit of the doubt, since trust can sometimes be created out of nothing, spontaneously, by giving it away freely and in a recklessly good way. Trust is often a form of blind belief, and like so many of the weak foundations on which humanity stands, someone has to take the first leap of faith.

Leave a comment